|

Meredith Williams, Principal NRHS

A pervasive challenge instructional leaders face in the classroom and through remote learning are those moments when students fail to meet the teacher’s expectations. Teachers cringe as they watch students struggle to express themselves in writing, shy away from interpreting vocabulary-dense test questions, and fail to maintain a neat notebook or device. Teachers grimace as they receive assignments that are past due, incomplete, or sloppy. Teachers fall into despair as students exhibit disruptive behaviors or refuse to engage in the learning task. Most often these challenges result in failing grades. As teachers, it is easy to analyze such failure to meet expectations as an inherent character flaw, labeling students as lazy or not academic. However, a keen teacher will step back from the situation and seek, not to assign labels and blame, but to identify root causes of the failure. In doing so, the teacher will often discover that the students’ products and actions often have very little to do with content knowledge. Students who don't participate, who don't turn in strong work, and who misbehave may do so because they need to be intentionally and lovingly taught key skills like agency, communication, organization, pacing, questioning, how to interact with peers, and how to interact with adults. This need for knowledge, far beyond the prescribed curriculum, tends to catch many teachers by surprise. For example, the math teacher finds, in addition to the quadratic equation, they must intentionally teach their students organizational skills, logical thinking, and metacognition. The biology teacher doesn’t instruct on just the standards of the biology final exam. Rather, successful biology teachers find they must model collaboration in lab experiences, research skills, and methods of data analysis. Teachers become instructors of a vast array of content, far beyond the scope of their content standards because we accept the challenge of preparing students for life, not just the next class. At NRHS we generalize these skills into Communication, Collaboration, Creativity, Critical Thinking, and Agency. Here are the rubrics we use to define what strong skills in each of these areas looks like. These are the rubrics our design teachers use for grading. Those teachers for whom students “just don't do anything" or have lots of behavioral issues are most often the teachers who have not accepted that they must teach more than content. The truth is, we have all been one of those teachers at one point or another. In their article Assuming the Best, Smith and Lambert write: Whenever students walk into the classroom, assume they hold an invisible contract in their hands, which states, "Please teach me appropriate behavior in a safe and structured environment." The teacher also has a contract, which states, "I will do my best to teach you appropriate behavior in a safe and structured environment." Scaffolds in a lesson allow the teacher to weave together key life skills with their content. The English teacher provides a template for interviewing the visitor and in doing so, models for the student how to appropriately ask questions and greet a guest. The science teacher asks students to observe their peers completing the lab measuring task and provide “glow and grow” peer feedback, effectively teaching students how to observe, reflect, and offer kind feedback for growth. When the teacher receives late work, she sits down with the student on the next assignment to set mini-check-ins, thus instructing the student on time management and building agency. The student submitting incomplete work is given a rubric and a highlighter and asked to score themselves and make necessary revisions before submitting the final draft. Scaffolding often feels like the teacher is doing for the student what they should be doing for themselves. The challenge is to recognize when students honestly do not know how to “do for themselves.” This is when the role of teacher becomes so important and overarching. It is in these moments, when teachers teach more than the content and help students develop skills that endure through life, that we achieve our purpose at NRHS. It is in these moments that we assure students have skills to propel their True North forward on a pathway of success.

42 Comments

Meredith Williams, Principal NRHS

As classes begin again this fall we also reboot our discussions at NRHS around authentic learning, which we define as real learning for the real world. As an academic community we have recognized that most of traditional “schooling” is nearly the opposite of what we do in the real world. In the ivory tower of school we often stay tucked away in a paradigm of theory where multiple choices are provided, word banks are offered, and the singular right answer actually exists. But in the real world there is rarely the one right answer, and seldom do questions come only after someone has fully explained the concept. Traditionally, as educators, we worked diligently to make the experience of “school” unreal. Teachers broke down concepts to the point that students needed only to follow their steps to the correct answer. Classes and schedules were established so no two contents would interfere with one another, and equivalent time to the minute was provided for each. Then we began to wonder if our graduates could survive and thrive in the real world. We considered whether the education they’d been provided was enough to sustain them in a world that is so different from the pattern of their schooling. An Alternate Approach But it wasn’t always this way. Prior to the advent of factory model schooling most trades were taught through apprenticeship. Those who wished to learn a skill or trade would spend weeks and years immersed in the actual practice of the skill in the real world with a master of the craft - a mentor who could guide them. In the apprenticeship method, the real world and the world of education coexisted in the same time and space. The learner contributed to the work of the master craftsman while the master craftsman contributed to the education of the learner. They grew and developed together: the craftsman, the apprentice, and the craft. At North High our goal is to bring more authenticity to the learning of our students. We want to adopt the apprenticeship mindset whereby students engage in the real world, and as educators we move along with them developing our craft together into something which we will give to the world. We make this shift by focusing on the work we ask students to engage in. We call the work that is truly for the real world or mimics as closely as possible the real world authentic. Methods of Working Authentically Technology allows our students the ability to create and interact socially with the real world in ways we might not have imagined only a few years ago. Our students now make videos and iBooks almost daily. They will be curating their individual work utilizing pages through Adobe Spark and collectively on our school social media sites throughout the year. But technology is not the only way our students will reach into the real world. We accentuate field trips, expert visits, and community connections. By the tenth day of school half our student body will have already traveled off campus for at least one educational exploration. We value the experience of our students exploring new parts of our community, and we find our community values the experience of meeting our students. Such strategies allow us to break down the factory model to build a more personalized apprenticeship paradigm. As we move through the year and our instructional designers (teachers) push the boundaries of authentic work they are sure to discover more techniques for putting the real world and education in the same time and space. As we do, they will share their experiences here so that you might be inspired to find your own ways of blurring the lines between “schooling” and the real world. Meredith Williams - Principal NRHS

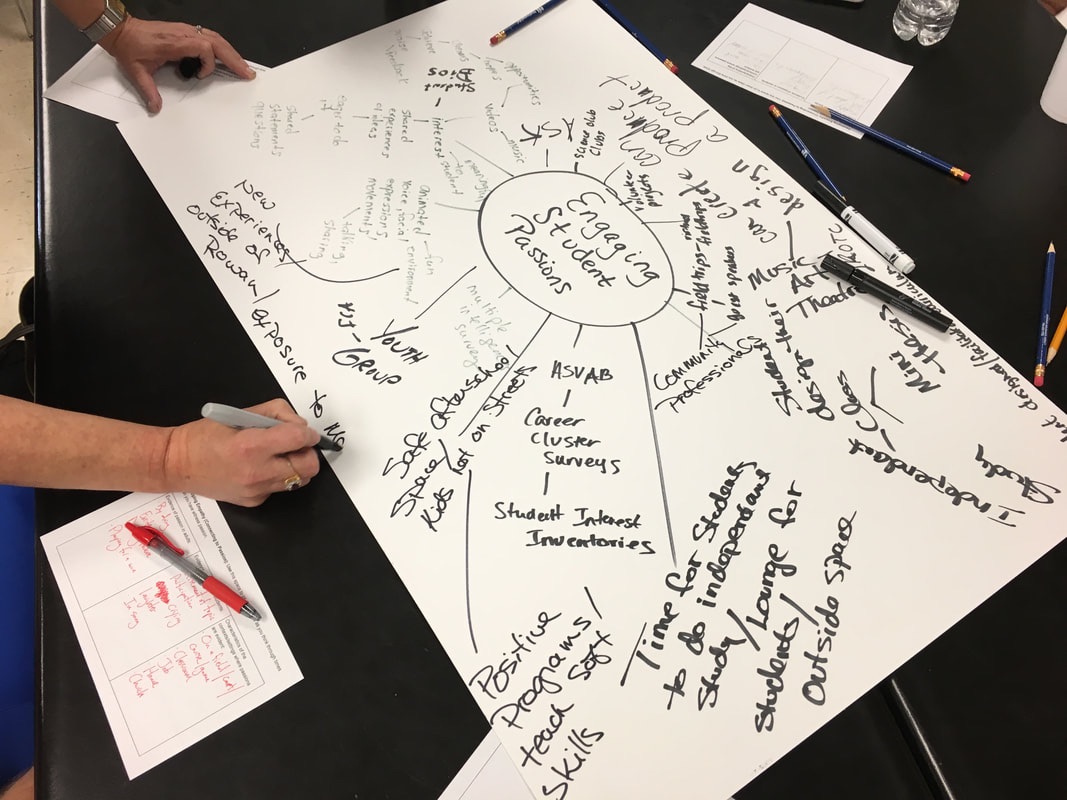

I’m often asked, “How does Design Class prepare students for college?” Perhaps the workflow of solving real-world challenges with open-ended solutions is so different from the memorize-and-bubble process of our traditional classrooms that we struggle to see how his process experience can prepare one for embarking on post-secondary education; whether a 4-year or other advanced degree. A few logistical details are important to remember in terms of our design lab. First, the course counts for two credits: a local elective Honors Design Lab and a Career and Technical elective, career or project management. Students still take at least four core classes in their schedule. Some students elect to add upper level and Advanced Placement courses to their schedule as well. Design class, therefore, co-exists with core curriculum. Teachers collaborate to connect and apply core content to the design challenges. However, the focus of the design class is not to learn more core knowledge, but to develop the essential life skills which we refer to as the 4C’s (collaboration, communication, creativity, critical thinking) and agency. In planning for transformation, teachers at North High were asked to share the most important thing they taught. Almost all responded with ideas that fit into the general 4C categories, such as time management, responsibility, or self-expression, rather than content knowledge. However, these are skills we do not explicity teach. We assume that students will learn these key life skills as we move through the formal core content curriculum. But, in fact, we rarely instruct students on how to improve in these essential life skills during core content classes. Therefore, we believe our Design Class, which focuses on and expects demonstration of these important skills, does more than any other class to prepare students not only for college, but for the “real world”. We want to graduate students who not only have academic knowledge, but who can think for themselves, who know how to actively learn, and who can work with others to achieve goals. We want to graduate students who will not be limited by the ideas of others, but can contribute in their families and communities through creative solution building. We understand students are more likely to develop and hone these skills when provided opportunities to learn, apply, and reflect on their growth. At NRHS, we use Design Class to provide this critical piece of the learning process and believe our students will be exceedingly prepared for living toward their True North because of the instruction we provide in this setting. Benjamin Butchart - 9th grade Design Teacher

In the 9th grade design lab we use rubrics for soft skills from New Tech Network and Buck Institute for Education. The four main soft skills we are assessing for growth are collaboration, written and oral communication, creativity and critical thinking. We embed these rubrics into our Learning Management System Schoology so that they can be added to an assignment. For example, when students write the story retelling the path taken by their group in their challenge, we use the rubric for written communication on the assignment. When we review and score a challenge story, we are looking for specific elements in the writing, like the ability to develop ideas, organize the structure of their writing, and skillfully communicate ideas through their writing. The rubric we score for students on Schoology allows students to receive specific feedback on their work. We also pull elements or lines from each rubric and make custom rubrics for specific assignments. We use these types of custom rubrics to create questions for students to discuss in reflection videos. The reflection video is a powerful artifact of learning that can be scored to assess a student’s ability to utilize the soft skills. The teacher considers the language from the rubric when creating a discussion question, so listening for evidence in the student’s video recording is a straightforward process. The subjective nature of measuring soft skills is quite different from the typical quantitative assessments we had been accustomed to in traditional classroom teaching. It has taken some time for us, as instructional leaders, to feel comfortable with the more subjective approach, even when solid rubrics are in place. When looking at measuring growth in soft skills, it is important to not get too hung up on the grading - because something wonderful happens when students reflect, and it’s hard to describe or measure what you hear and see - a moment of silence, right there on the video reflection. The silence when a student stops speaking, thinks about what they want to say, how they want to say it, how something happened, or what they did, and then begins speaking again is important. After the silence, the student more eloquently describes how they used a soft skill to solve a challenge. Maybe this moment just has to be experienced or reflected upon itself to see the power in it - a learning moment, when students get closer to becoming a master of words - and masters of themselves. |

AuthorsThe Design Classes at North High are taught by four educators: Alexis Greer and Benjamin Butchart in 9th grade and Miranda File and Brian Whitson in 10th. These teams lead the CBL and design thinking approaches at North Rowan High. Archives

July 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed